Have you ever thought that ADHD and autism could perhaps be the same disorder? – Or have you thought that they are way too different, two different planets in the psychiatric universe? Researchers do not agree on this. We know that both ADHD and autism are neurodevelopmental conditions with onset in childhood and that they share some common genetic factors, however, they appear with quite different phenotypical characteristics. We also know that people with ADHD or autism have an increased risk of getting other psychiatric disorders, so-called comorbidities, and smaller studies have shown that individuals with ADHD or autism get different psychiatric disorders, and at a different degree.

How can we utilize this knowledge about different psychiatric comorbidities between ADHD and autism? How can we get closer to an answer to this question; are ADHD and autism similar or different conditions? By using large datasets; unique population-based registries in Norway, we wanted to compare the pattern of psychiatric comorbidities in adults diagnosed with ADHD, autism or both disorders. In addition, we wanted to compare the pattern of genetic correlations between ADHD and autism for the same psychiatric traits, and for this, we exploited summary statistics from relevant genome-wide association studies.

In the registries, we identified 39,000 adults with ADHD, 7,500 adults with autism and 1,500 with both ADHD and autism. We compared these three groups with the remaining population of 1.6 million Norwegian adult inhabitants without either ADHD or autism. The psychiatric disorders we studied were anxiety, bipolar, depression, personality disorder, schizophrenia spectrum (schizophrenia) and substance use disorders (SUD).

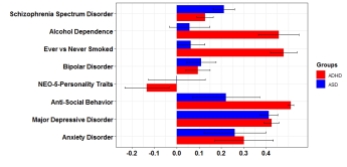

Interestingly, we found different patterns of psychiatric comorbidities between ADHD and autism, overall and when stratified by sex (Fig.1). These patterns were also reflected in the genetic correlations, however, only two of the six traits showed a significant difference between ADHD and autism (Fig.2).

Figure 2. Left: The pattern of prevalence ratios of psychiatric comorbidity in adults with ADHD or autism observed in this study (ADHD; n=38,636, autism; n=7,528). Right: genetic correlations (rg) calculated from genome wide association studies. Psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent in both ADHD and ASD, with schizophrenia being most prevalent in ASD and antisocial personality disorders in ADHD. Genetic correlations are also high with both disorders, with especially high correlations between ADHD and alcohol dependence, smoking behavior and anti-social behavoiur. Major depressive disorder has high genetic correlations with both ADHD and autism. Figure from Solberg et al. 2019, CC-BY-NC-ND.

The most marked differences were found for schizophrenia and SUD. Schizophrenia was more common in adults with autism, and SUD more common in adults with ADHD. Associations with anxiety, bipolar and personality disorders were strongest in adults with both ADHD and autism, indicating that this group of adults suffers from more severe impairments than those with ADHD or autism only. The sex differences in risk of psychiatric comorbidities were also different among adults with ADHD and ASD.

In conclusion, our study provides robust and representative estimates of differences in psychiatric comorbidities between adults diagnosed with ADHD, autism or both ADHD and autism. With the results from analyses of genetic correlations, this finding contributes to our understanding of these disorders as being distinct neurodevelopmental disorders with partly shared common genetic factors.

Clinicians should be aware of the overall high level of comorbidity in adults with ADHD, autism or both ADHD and autism, and the distinct patterns of psychiatric comorbidities to detect these conditions and offer early treatment. It is also important to take into account the observed sex differences. The distinct comorbidity patterns may further provide information to etiologic research on biological mechanisms underlying the pathophysiology of these neurodevelopmental disorders.

This study was done at Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen Centre for Neuropsychiatric disorders, University of Bergen, Norway, and published OnlineOpen in Biological Psychiatry, April 2019, with the title:

“Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity and genetic correlations provide new insights into differences between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder”. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.04.021

Figure 1 and 2 are re-printed by permission https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

Berit Skretting Solberg is a PhD-candidate at the Department of Biomedicine/Department of Global Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Norway. She is also a child- and adolescent psychiatrist/adult psychiatrist. She is affiliated with the CoCa-project, studying psychiatric comorbidities in adults with ADHD or autism, using unique population-based registries in Norway.