New research shows that mindfulness as a treatment for ADHD, also brings forth insight, acceptation and improved relationships.

This post is also available in Dutch.

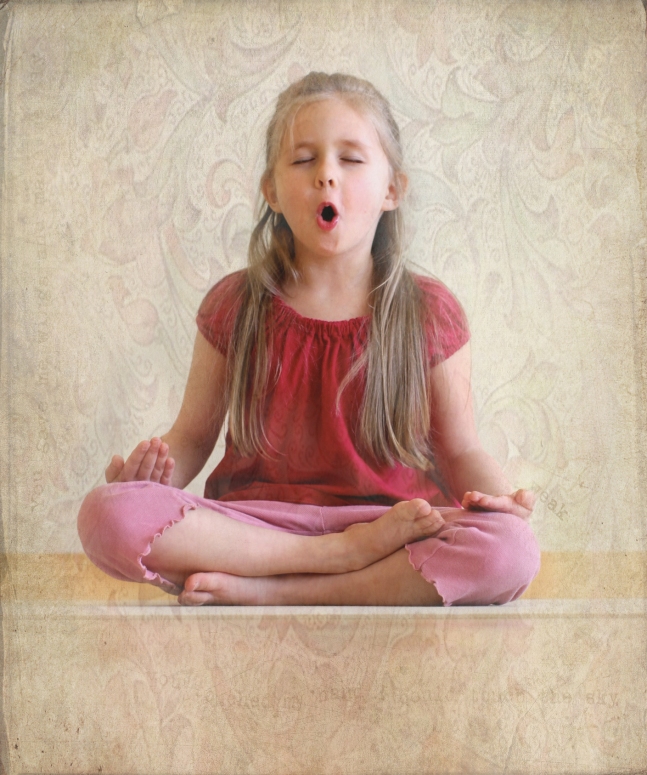

Mindfulness is being investigated as a new treatment for children with ADHD. The question that rises often is whether the inattentive and/or hyperactive/impulsive behavior decrease after the training. However, the training can also have other effects on children and their parents, and these can differ greatly.

Attention can be trained

ADHD is a diagnosis characterized by symptoms of an attention deficit and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity that can lead to severe impairments in daily functioning. With mindfulness meditation you can train “your attention-muscle”: Over and over you need to focus your attention on what you are experiencing now. This happens with a friendly and curious attitude, without labeling the experiences as good or bad and without reacting to them immediately. From previous studies, we know that ADHD-symptoms – especially inattentiveness – can decrease because of mindfulness meditation, but these studies used small samples and did not make use of a comparison group.

MindChamp study

Is an 8-week mindfulness training for children with ADHD and their parents a good addition to care as usual? We investigated this with the MindChamp project with more than one-hundred participating families the first big, rigorous study in this area. With some of these families we additionally did extensive interviews to make an overview of the hindering/helping factors of mindfulness training as well as the scope of different treatment effects. The results of these interviews with 20 parents, 17 children (9-16 years old), and the 3 mindfulness trainers have recently been published in a scientific article.

What did and did not help in the mindfulness training?

Participation was rated as positive. Parent and child were having quality-time together, helped each other and learned “a common language”. Both parents and children felt supported by other group members. Sharing experiences led to feeling recognized.

“There I was not different, but just the person I am and so were the other kids”– girl, 9 years old

It was both difficult and informative when group members were too disturbingly present. Many found the non-judging, friendly attitude of the trainers a relief, others would have liked more interference from them. The children could collect points by making assignments at home for which they received a reward from their parents. For some this was very helpful, for others stressful. In addition, sessions were experienced as a bit too long by children, it requested quite some time and energy investment. Nevertheless, most parents recommended the training.

Which treatment effects were experienced by children and parents?

The experiences differed. Some children and parents noticed that they reacted less heavily, or less impulsive, which led to a decrease in fights. Many were talking of more calmness and relaxations. These effects went beyond the context of the training itself and were for instance noticeable at school. Some families noticed little to no effect on ADHD symptoms and/or cognitive functioning of the child, but did experience effects in other domains. Many also experienced a better parent-child relationship, and better relations with others. The training brought awareness, insight, and acceptation (of self and others).

“I see better and better how he approaches things and what kind of help he needs”– father

Take-home message

When we only look at the (average) effect of the treatment for the entire group, we may miss very valuable information. It is important to not only investigate the effects on ADHD-symptoms, but also other effects ánd individual differences. The training for instance gave more insight, acceptation and improved relationships. We hope that our study leads to more insights into how mindfulness can be used for children with ADHD.

Photo by Jude Beck via Unsplash

Author: Nienke Siebelink

Buddy: Floortje Bouwkamp

Editor: Ellen Lommerse

Vertaling: Jill Naaijen

Editor vertaling: Felix Klaassen

This blog was originally published on www.blog.donders.ru.nl. This is the official blog of the Donders Institute on brains and science.

Image from:

Image from: