Psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, major depression or bipolar disorder, often overlap and occur together. For example, individuals with ADHD on average experience twice as many depressive symptoms as the general population without ADHD [1,2]. In addition to the distress and impairment that is brought on by a single psychiatric condition, having multiple conditions can hugely increase the severity of symptoms and hinder treatment. To better understand why these disorders overlap, we investigated the genetic risk factors that are shared among psychiatric disorders, and found several genes that play important roles in regulating two signaling-mechanisms of the brain: dopamine and serotonin [3].

Dopamine and serotonin are two important neurotransmitters (messengers molecules that transmit messages between brain cells) that control a wide range of essential functions in your brain (e.g. controlling your movements, cognition, motivation, regulation of emotions, and responding to reinforcement and reward). For that reason, alterations in these two systems have been related with the physiopathology of several psychiatric disorders, and also have been pointed as possible therapeutic targets for them.

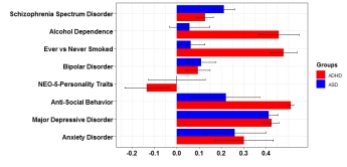

We systematically explored the contribution of common variants in genes involved in dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission in eight psychiatric disorders (ADHD, anorexia nervosa, autism spectrum disorder , bipolar disorder, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia and Tourette’s syndrome) studied individually and in combination. To do so, we used data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC, https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/) to explore the entire genome in thousands of patients with different psychiatric conditions, which were compared with controls (individuals without any psychiatric condition).

In this way, we could identify variations in genes (and in groups of related genes) that confer susceptibility to a given disorder. For example, a gene named CACNA1C that is involved in the connectivity between brain cells, was found to contribute to both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Using this approach, we found 67 dopaminergic and/or serotonergic genes associated with at least one of the eight studied disorders, and twelve of them were associated with two conditions. Interestingly, five out of these twelve genes, including CACNA1C, belong to both the dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmitter systems, highlighting the importance of those genes that participate in both systems and their high interconnectivity. Next, we analyzed groups of genes that work together, and found that the dopaminergic genes have an important role in ADHD, autism, depression, and in the combination of all of the eight disorders that we studied. We also found that the group of serotonergic genes are relevant for the overlap between depression and bipolar disorder.

These results support the existence of a set of dopaminergic and serotonergic genes that increase the risk of having multiple psychiatric conditions. Having identified these genes, the next step is to investigate if any of these could be targeted by new drugs that directly influence specific parts of the dopaminergic or serotonergic system, compared to the more unspecific drugs that currently exist. That would be an important step for treating psychiatric comorbidity.

If you want to know more about this research, you can read our publication here.

This blog was written by dr. Judit Cabana-Domínguez. She is a postdoctoral researcher of psychiatric genomics at the Vall d’Hebron Research Institute (VHIR). The work described here is part of the CoCA project on comorbid conditions of ADHD.

References

- McIntosch et al. (2009). Adult ADHD and comorbid depression: A consensus-derived diagnostic algorithm for ADHD (nih.gov) Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 5: 137-150. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s4720

- Di Trani et al. (2014). Comorbid Depressive Disorders in ADHD: The Role of ADHD Severity, Subtypes and Familial Psychiatric Disorders (nih.gov) Psychiatry Investigation, 11(2): 137-142. doi: 10.4306/pi.2014.11.2.137

- Cabana-Domínguez et al. (2022). Comprehensive exploration of the genetic contribution of the dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways to psychiatric disorders. Translational Psyciatry, 12(1): 11. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01771-3